STOP PRESS (6.6.25): The President of the KBD has his say: [2025] EWHC 1383 (Admin)

One of the sobering experiences of training to be a lawyer – the dawning realisation that it isn’t all dramatic cross-examination and fighting for the underdog – is legal research. Like learning a new language (let’s say, German), it’s a long and often tedious process. Some trainees, admittedly, seem to enjoy the tedium more than others. I was firmly in the ‘not enjoying this tedium’ camp.

My own experience as a pupil in the mid-90s involved a mixture of the mundane and the complicated.

Mundane: going to the law library to find the authority, going back to the law library to find the correct authority (Official Law Report best, then All England, then FLR etc.) and the endless photocopying: should it be one or two pages of judgment per page of photocopy? An outsider might be surprised at the strength of senior lawyers’ views about zoom magnification and borders. So, back to the copier I would go, to fantasise about the claim I would bring against chambers for the damage to my retinas from exposure to all of the UV light. When this task was completed, then came creating bundles of authorities, making sufficient hard copies of my pupil master’s skeleton, and generally becoming dextrous with treasury tabs and tying red tape over briefs.

Complicated: developing an understanding of how the law works: the relationship between primary and secondary legislation, the concept of precedent (‘stare decisis’), and, above all, learning how to read a reported judgment. This may sound obvious to a non-lawyer, but it is often very difficult in considering a judgment to separate out the wheat (the binding ratio of a judgment) from the chaff (the non-binding comments, or dicta), particularly in a discretionary area of law such a family law.

In short, there were – and there are – no shortcuts to becoming a good lawyer and for all of the aforesaid tedium, this was all necessary and part of learning the essential craft of becoming a barrister (in my case), a solicitor or a legal executive.

Impact of internet and paperless working

Over time, some of these mundane tasks have become redundant. The photocopiers which were once the engine room of chambers now lie almost dormant. A trainee’s daily step count is, I suspect, a fraction of what it used to be: nowadays, there is rarely any need to leave the office or visit a law library, with the attendant opportunities for dragging one’s feet and stopping to have a cigarette. Practically everything is online, ranging from (eye-wateringly expensive) subscriptions to practitioner text books and law reports to the free resource of court judgments on BAILII and the National Archives.

While BAILII and the National Archives are tremendous legal resources and exercises in open justice, they should be used with the following health warning in mind: these judgments are, in effect, raw material. They have not been curated by professional law reporters who have summarised the essential facts and the ‘ratio’ in the headnote.

Many of the judgments that appear will have no value as precedents and cannot properly be cited (see my earlier blog, ‘What’s the Point of A Judgment‘, which should now be read with the recent retrospective approval of a handful of FR cases (see https://financialremediesjournal.com/vertix/citation-guidance.htm)

While the impact of the internet has been hugely positive in some areas (notably how quickly legal research can be undertaken), the free availability of judgments creates its own problems: reliance on inadmissible authority, not applying the rules of precedent, failing to distinguish the ratio from the dicta. To put it bluntly, a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

Just as there are no short cuts to learning German (despite building up a long streak on Duolingo) there is no short cut to becoming a good lawyer.

AI

And then came Artificial Intelligence. At some point in 2023, instead of being asked ‘How can you represent a client who is guilty?’, lawyers at social occasions would be asked, ‘Will AI replace you altogether?”. For the record, the model answer to these questions is “I don’t do criminal law, and I’m not the judge, but if I did, it would be fine provided I’m not misleading the court”, and ‘Not yet, but a lot of ‘legal work’ is bound to become automated. It’s difficult to see how AI would ever be able to provide legal advice but then again, we’ve all seen the film Terminator…”

I have dabbled with ChatGPT and found it quite impressive in some areas. Open questions like “should I take my dispute to court?” or “should I always trust my barrister?” elicited impressive answers which covered points such as proportionality, delay, a barrister’s professional duties to the court and client, the assessment of evidence etc. I then asked “why are English judgments anonymised?” and ChatGPT instantly provided me a comprehensive ten point response, at the sort of level I would expect from a trainee who had been given a couple of hours to think about the question.

AI Hallucinations

Out of interest, I then asked “What are the leading cases in financial remedies”, and AI suggested a case I had not heard of before, decided in 1996 which dealt with the overarching objective of ‘fairness’.

This was both surprising and anachronistic – because that principle arose from the later case of White [2000] UKHL 54. The proffered case title, which seemed plausible, turned out not to exist. The machine learning behind AI had invented a case: a superficially plausible case with what appeared to be a correct neutral citation but a false one nevertheless. Jennifer Lee has written an excellent article on these AI ‘hallucinations’ (‘Fabricated Judicial Decisions and Hallucinations‘)

Legal research, as described above, can be a slow and tedious process. In the last decade we have all come to rely on the internet instead of the law library as the repository of statute law, judgments and (for those who can afford it) practitioner text books. Thanks to the internet it is infinitely quicker to undertake legal research and there is an obvious temptation given the pressures of time to take the short cut of quoting from an online blog or using AI.

But here lies the real danger…

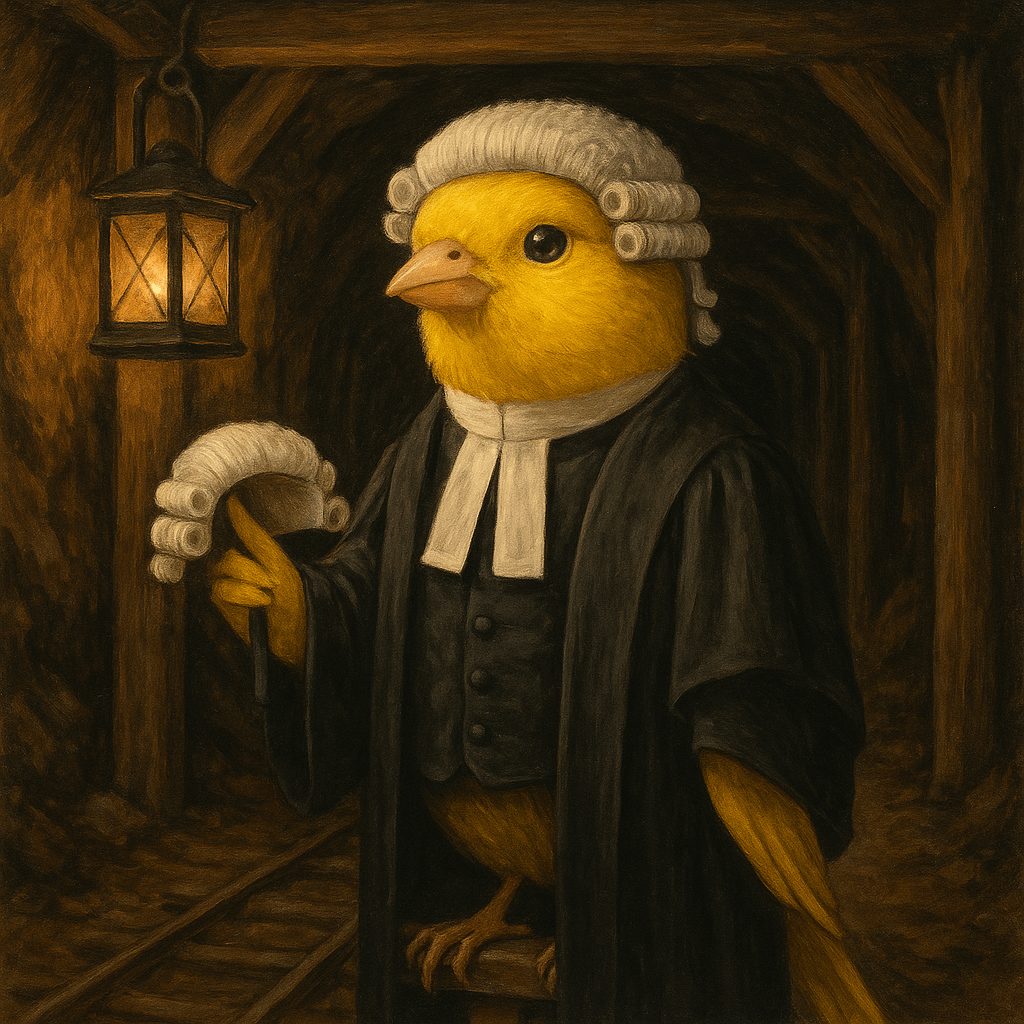

The canary in the mineshaft: R (Ayinde) v LB Haringey

On 30 April 2025, Mr Justice Ritchie handed down judgment in the above case [2025] EWHC 1040 (Admin), which arose out of a claim for homeless accommodation under s. 188(3) of the Housing Act 1996. Ritchie J dealt with two applications: (1) relief from sanctions and, notably, (2) a wasted costs application made against the claimant’s barrister and solicitors. The latter application, which is relevant to this blog, concerns a barrister (who I will not name, although she is named in the judgment) who cited five cases that it turned out did not exist.

My attention was first drawn to this case from two outstanding articles which set out the facts in greater detail, from the perspective of a housing lawyer (Giles Peaker’s Nearly Legal ‘The cases that weren’t) and a general civil lawyer (Gordon Exall’s Civil Litigation Brief, ‘When Cases Relied Upon…Were Simply False’, both of which I would strongly recommend for a more detailed consideration of the legal issues.

The essential facts of the ‘wasted costs’ application were as follows:

- The claimant’s statement of facts and grounds for a judicial review contained references to five non-existent cases (‘fake cases’ to adopt Ritchie J’s phrase);

- When the defendant local authority sought copies of these authorities, they were palmed off in the following terms from the claimant’s solicitor (who, it should be noted, operate as a charitable law centre):

“there could be some concessions from our side in relation to any erroneous citation in the grounds, which are easily explained and can be corrected on the record if it were immediately necessary to do so. What you have not done is to refute the veracity of the points and legal arguments that prevailed against your position and any failures of your client to measure up to its obligations under the 1996 Act… let us agree that the citation errors can be corrected on the record ahead of our April hearing. Apart from adding our deepest apologies, we do not consider that we are obliged to explain anything further to you directly. You may better serve your organisation by giving attention not to the normative discoveries you have made, but whether you can locate the authorities in support of the points raised, which points you are clearly in agreement with“

- This correspondence was condemned by the court in the strongest terms:

[46] That was, I must say, a remarkable letter. I do not consider that it was fair or reasonable to say that the erroneous citations could easily be explained and then to refuse to explain them. Nor do I consider it was professional, reasonable or fair to say it was not necessary to explain the citations. The assertion that they agreed to correct the citations before April never came true, for they never did. The assertion that no further explanation or obligation to provide an explanation was necessary or arose is, in my judgment, quite wrong. Worst of all, the assertion that the citations are merely cosmetic errors is a grossly unprofessional categorisation.

- In court, counsel gave the following explanation for her reliance on the five fake cases;

“[53] …she kept a box of copies of cases and she kept a paper and digital list of cases with their ratios in it. She dragged and dropped the case of El Gendi from that list into this document. I do not understand that explanation or how it hangs together. If she herself had put together, through research, a list of cases and they were photocopied in a box, this case could not have been one of them because it does not exist. Secondly, if she had written a table of cases and the ratio of each case, this could not have been in that table because it does not exist. Thirdly, if she had dropped it into an important court pleading, for which she bears professional responsibility because she puts her name on it, she should not have been making the submission to a High Court Judge that this case actually ever existed, because it does not exist. I find as a fact that the case did not exist. I reject [her] explanation”

- Matters proceeded to become worse for counsel:

“[55] What [counsel] says about this twice in submissions was that these are “minor citation errors”. When I challenged her the first time she backtracked on that and accepted they are serious. However, in her later submissions she returned to them being “minor citation errors”. She said there was no dishonesty and submitted that there was no material prejudice. Then she sought, remarkably, without having put in a bundle of authorities or anything in writing, to provide in submissions references to further cases which she did not put before the court, which she says made out the principles that she had put out in each paragraph containing the fake cases.”

“[58] The problem with that paragraph was not the submission that was made, which seems to me to be wholly logical, reasonable and fair in law, it was that the case of Ibrahim does not exist, it was a fake. I do find this extremely troubling. I do not accept [counsel’s] explanation for how these fake cases arose. I do not accept that she photocopied a fake case, put it in a box, tabulated it and then put it into her submissions. The only other explanation that has been provided before me, by Mr Mold, was to point the finger at [counsel] using Artificial Intelligence. I do not know whether that is true, and I cannot make a finding on it because [counsel] was not sworn and was not cross examined. However, the finding which I can make and do make is that [counsel] put a completely fake case in her submissions. That much was admitted. It is such a professional shame. The submission was a good one. The medical evidence was strong. The ground was potentially good. Why put a fake case in?”

…

[63] [Counsel] had moved on from fake High Court cases to fake Court of Appeal cases. I have no difficulty with the submission that the Respondent local authority had to ensure fair treatment of applicants in the homelessness review process, but I do have a substantial difficulty with members of the Bar who put fake cases in statements of facts and grounds.

[64] I now come to the relevant test. Has the behaviour of [counsel] and the Claimant’s solicitors been improper, unreasonable or negligent? I consider that it has been all three. It is wholly improper to put fake cases in a pleading. It was unreasonable, when it was pointed out, to say that these fake cases were “minor citation errors” or to use the phrase of the solicitors, “Cosmetic errors”. I should say it is the responsibility of the legal team, including the solicitors, to see that the statement of facts and grounds are correct. They should have been shocked when they were told that the citations did not exist. [Counsel] should have reported herself to the Bar Council. I think also that the solicitors should have reported themselves to the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I consider that providing a fake description of five fake cases, including a Court of Appeal case, qualifies quite clearly as professional misconduct.”

The court proceeded to make a wasted costs order against counsel and solicitor. One cannot help but think that a more experienced advocate would have either admitted the seriousness of the problem sooner or not made matters worse by proffering an explanation which the court rejected and found ‘extremely troubling’.

Conclusion

On a personal level, it is possible to feel sympathy for a very junior member of the Bar who appears to have taken a shortcut and relied on case citations seemingly thrown up by AI. While there was no factual finding to that effect, it is difficult to conceive of another explanation. And this problem is likely to recur, particularly in cases involving litigants in person.

There clearly was no attempt on her part to present a dishonest argument: the problem was that counsel was relying on fictitious cases rather than having undertaken proper legal research and found the actual cases in support.

This case has naturally drawn significant interest and the making of a wasted costs order, with the prospect of disciplinary proceedings, is little short of a professional nightmare.

However, Ayinde illustrates a number of broader points which are of general application, i.e.

- The dangers of taking short cuts and relying on AI. Put simply, AI should either not be used at all, or should be used with the greatest possible care (with all authorities double checked and produced);

- The seriousness with which a court will approach these issues when they arise;

- Any lawyer proceeding in this way, making reference to cases that have been generated (hallucinations) will face the risk of wasted costs, public exposure (through publication of judgment online) and potentially disciplinary proceedings, regardless of whether the argument is properly made or not.

Ultimately, just as one cannot learn German by spending five minutes a day on Duolingo, one cannot litigate (certainly not in front of a High Court Judge) by taking the shortcut of using AI to do one’s legal research.

Alexander Chandler KC

8 May 2025

PS I am aware of the irony of having used AI to create the above image.